As has happened several times, le petit garçon unwittingly steered me to this month’s blog topic, just by attending school each day. First it was French poetry, next a filmmaker; I won’t be surprised if I soon write about marbles, which are the thing on French playgrounds for the under-eight set. But more on that another time.

I leapt at the opportunity when his teacher asked if any parents would be willing to chaperone the class on a field trip. I love to observe the kids together with their maîtresse, listen to how they talk and interact, and discover new corners of Toulouse.

I was especially excited because this was an exhibition by a Franco-American artist who, I learned upon a little research, was born in Pasadena and moved to France as a child. I imagined all the stuff she and I would have in common, the conversations we might have. I pictured her, oozing Californian cool and free-spiritedness while speaking perfect French.

Maybe, maybe not. But I also had a hunch too that there was something for me there. Something to uncover, to be reminded of, inspired by perhaps. Maybe, I thought, it will stoke a fire in me.

Part of month-long slew of contemporary exhibitions around Toulouse, a biennial festival titled Le Printemps de September (OK, yes, maybe we are a bit tardy), Nina Childress’ show was held at the small Musée Paul Dupuy just off Rue Ozenne. It was two days from opening; our tour would be a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the work-in-progress. My mouth watered.

So one afternoon, we cheerfully herded 22 five-to-seven-year-olds through the park and to the museum, where a friendly guide welcomed us.

Childress had dug out works from storage at the larger Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, ones made by minor, forgotten, or less-loved artists that caught her attention for formal or thematic reasons. Her interest sparked, she planned to then associate forty of them with thirty of her own. And today, she’d generously agreed to have a herd of curious enfants trample into her construction zone.

As we waited for our tour I peered through a glass door on my right to see a bunch of the museum’s paintings, anticipating their moment in the spotlight. Out of context like this, they seem so modest and ordinary. How does putting a museum object on the floor, versus a pedestal for example, affect our experience and our critique of it?

|

| This one, for example? |

We were greeted at the exhibition entrance by the artist at work, bralessly unpretentious in an orange t-shirt splattered with paint, carrying a roll of blue painters’ tape. Her glasses were thickish, smudged; she seemed to peer through them at us, as if through fog.

She began by explaining the opening sign, painted in rough letters, its paint dribbling deliberately.

|

| Apparently the owl also finds its young beautiful . . . |

…which, I thought, must imply that every parent finds its children beautiful? OK, that’s sweet, and true, I thought, right? Babies — adorable to every mother’s eye, and thank god for that. Apparently this was a fable her own mother repeated to her, about an owl who, in an effort to protect her young from a dangerous and hungry eagle, effused about how beautiful her babies were. Really built them up. So much so that when the eagle saw them, it didn’t recognize them by the owl’s description — perhaps their faces only their mother could really love? — and so devoured them as planned.

Childress was, as my helpful guidebook told me, building her own nest of sorts at the museum and “brooding over the chicks’ revenge”. Retrieving paintings and finding something in even the most neglected among them. I think; to be honest, I’m still a little puzzled. Was she connecting the story with her own efforts on behalf of the unloved paintings? Was she critiquing the portrayal of women in painting and sculpture? If so, how does that connect with the owl story? Or is it more of an institutional critique — rethinking the museum itself?

As it turned out I got too busy being captivated by the physical experience of the exhibition to fuss with these questions for the moment. I was immediately entranced by the sea of brown craft paper, covering the walls. Torn bits here, plastic sheets with quick sketches of precious 17th-century portraits there. People busily worked around us, discussing placement, mounting, lighting. My questions multiplied. Was what we were seeing prep, or was it the exhibition itself?

We sat down with Childress, in the midst of the chaos, to chat. Scared her by nearly putting our sneakers on the freshly-painted black wall to our right, came perilously close to leaning on that painting on our left, propped against the wall.

We plied her with questions; she looked at us through her clouded lenses and fielded them, clearly distracted but still, remarkably, amiable. How did you start painting? How long does a painting take? Do you like animated movies? Do you ever draw on a tablet? When did you know you wanted to be an artist? Where is your studio? What inspires you?

Oh, she said, good question. It’s not what people think, artists aren’t what people think.

As we sit, my eyes wander to what she’s wearing, how she holds herself. She’s unassuming, not the least bit flashy. Unpretentious and hard-working, like her work, I think.

As I assess her physical presence, I wonder, Why am I so interested in how she looks? It dawns on me how deeply-set that is, this tendency to size a woman up based on her appearance. Even an accomplished artist who’s pouring hours and hours into a sizeable and meaningful project. I resist it, but it takes concerted effort: I sometimes still buy into the pervasive idea that looks are the ultimate statement about a woman’s value, long before the content of her ideas or character.

I refuse to go there. I want to concentrate on her work. But on the other hand, the artist’s persona, their public face, does fascinate me. How do they turn up? How do they present themselves to the public? Do they care? How do women embrace their bodies and at the same time refuse to be reduced to their appearance?

I hang out with that kōan.

I returned later in the week for the opening, breath baited, to see the completed show.

I was relieved to discover that the elements I loved — the paper, the roughhewn-ness — remained. More clear now was the conversation between her work and the museum’s. The torn paper on the walls, for example, echoed of one of the abstract paintings.

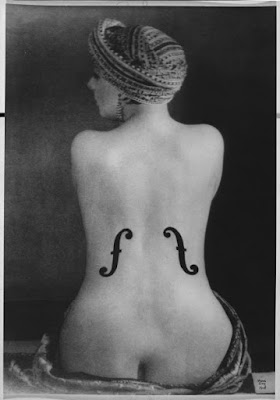

One section contained image after image of nudes being gazed at — hers and theirs. Some coyly aware, some utterly innocent to that weirdo peering out from behind the trees. A lot of breasts, here lovingly attended to, there aggressively painted. Damn they get a lot of attention, don’t they? As if they’re the defining female feature, or have some kind of structural significance.

The machismo in one museum piece was particularly appalling — men fully-clothed being served tea by a woman in her birthday suit, spare me — so she repainted it into abstraction. It might be my favorite: a reclamatory critical statement, and interesting in itself, simultaneously blurry and crisp.

|

| Mm hmm. Right. In your dreams. |

|

| It's not your eyes, nor my camera, I swear! |

The artist was present; she told me they’d finished just two hours before the opening. Aside from flash of turquoise blue toenails evoking her color palette and 70s-era imagery, she seemed unceremonial. Same knee-length blue jogging pants and sandals as before, now with a dark blue hooded sweatshirt, a blue backpack slung over her shoulder. Same clouded glasses.

She’s been working on this shit for days, I thought, and she’s finally done. She’s probably exhausted.

On my third and final visit, I had the gallery to myself. I appreciated again the deliberateness in every detail, even down to the splattered paint. I admired her range and versatility, crude here, polished there. I longed to work at a museum again so I’d have access to their trade secrets. I thought of volunteering to help install exhibitions. I wondered how long each piece had taken to create, and how that affected my thoughts about its monetary value.

Absent a curious friend or companion with whom to toss around ideas, I tried to practice the inquisitive approach I encourage in my students. What was I seeing? Why, for example, was this roll of what looked wallpaper cascading down the wall and spilling onto the floor? Kraft sur Kraft, Nina Childress, 2018.

What a delicious challenge, to curate an entire space, from the moment of entry to the rounding into the final gallery. Ensuring each space is its own but also part of a coherent whole. Precision even in the apparently sloppy bits. And in this case, a call to question what we assume is going to happen, given that this is a Museum, in whom we place our aesthetic trust.

I think of Duane Linklater’s 2015 salt exhibition at the UMFA, who took objects from the museum’s collection off their literal and proverbial pedestals and shone new light on them. How do museums shape our assumptions and opinions? Can they themselves address these challenging questions, including their own authority? As with the owl and the eagle and their view of the owlets, is the nature of reality dependent on the perspective from which it is observed?

This exhibition reconnected me to my craving to take over an entire space, from the moment one enters to how the walls are painted to how every sense is engaged. Like a piece of music: when you curate a full exhibition you could curate a journey. Make it practically irresistible.

My own work has found a temporary home in Toulouse, at Le Pic Saint-Loup till the end of the year. I love the way restaurants like this can address the space in its entirety, too, and tend to all your senses whilst offering what could appear on the surface to be just a (really, really good) meal.

You never know, with cafés and bars — the lighting can be shit or the whole thing can feel like a vague insult, to the place, the artist, the artwork, and all the work behind it. But at other places, like this one, even the toilettes are considered, with their hand towels, bunches of lavender, objects placed just so simply for pure visual appeal. We were expecting you, we haven’t forgotten you. Now get back to your gastronomically gorgeous repast.

Thank you Ms. Childress for pointing shit out and for working hard despite all the forces working against you. Including yours truly, who still struggles with the notion that, for women, appearance is what it all comes down to in some kind of absurd final analysis. Thank you for being smart, and strong, and hard-working, and kind-of witty, and for continuing your work. Maybe I'll write you a love letter, dammit.